ART WORLD NEWS

Blossoming artist: Damien Hirst on returning to the studio, fluorescent florals and the ‘muppets’ in government

[ad_1]

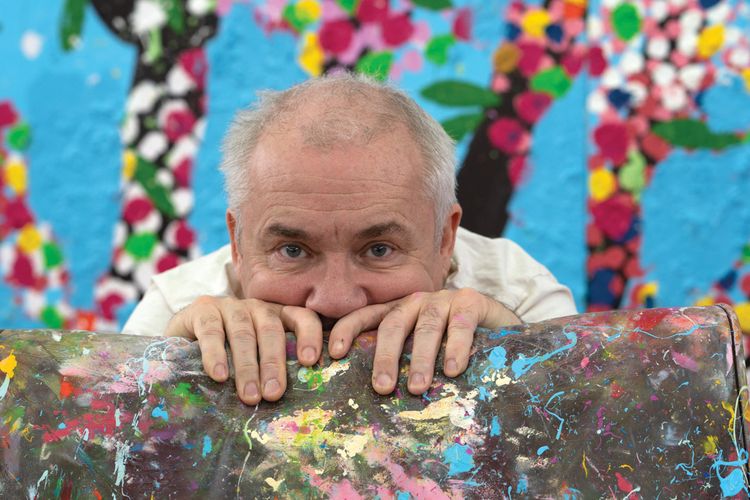

Damien Hirst in his studio

© Prudence Cummings

I visited Damien Hirst’s Thames-side Hammersmith studio on one of those peculiarly English damp, grey days to be greeted by a veritable burst of colour and a beaming Hirst, spattered in paint and clearly in his element. I am advised to don a rather fetching white shell-suit and slippers, just in case I, too, am transfigured by pigment, which dribbles Pollock-like across the floor and splashes sofas and surfaces. I am here to talk to Hirst about his return to the studio, after the intense and lengthy production phase of Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable, and to see his new series of cherry blossom paintings in progress. Some are still in their nascent, skeletal state—he describes these with gleeful irony as “bad versions of Hockneys”. Others are overloaded with splotches of blossom to a “celebratory” state of excess.

The Art Newspaper: As we’re sitting here surrounded by your new Cherry Blossom paintings, I’d like to ask about your return to the studio and to working without a cast of studio assistants. Did your Veil paintings presage this?

Damien Hirst: Well, no. Around the time that my friend Angus Fairhurst committed suicide in 2008, I was in the middle of painting. It was quite a dark little pursuit in a really claustrophobic space in my garden. So, I was painting those really dark blue paintings—they’re very derivative, like Bacon’s—and I was feeling like I was in 1953 and wondering what the hell I was doing. It got worse after my friend committed suicide. I got out of there because it got quite negative and I had a little studio in Claridge’s for a while.

Then, I started working on Treasures, really intensely. That became such a complicated thing with so many people and things and objects and fabricators. It just became a really crazy task at the opposite end of the spectrum. That thing where it says artists don’t make their own art, that was the pinnacle of that, really. Which I’ve never had a problem with: I don’t see the difference, whether you make it yourself or you don’t, as long as the end result is exactly what you want. Then I finished my work on Treasures over a year before the exhibition in Venice opened. It was all set in motion, so I was kind of twiddling my thumbs because I’d said what I wanted and I had to look at things, but very erratically. Everything was taking a long time. There were some carvings that took two-and-a-half years to carve, and I’d set them up a year-and-a-half before. So, I got this studio and thought, “I should just do some paintings.”

This studio?

Yeah. I rented this studio, just before Treasures, and then it just exploded when I got in here. I think the size of the painting was decided by the space. I wanted them small enough so that you still get the light above them, coming through the windows. What used to happen is, I’d make a painting and the galleries would come in, like it, and put one in an art fair. But that didn’t feel right. I thought I’ve got to complete the series and feel happy with everything first. And that was a new way of thinking for me. Now I make, fabricate, document, complete a series, and then work out what I want to do with it. So, you keep the creating away from the promotion or whatever. It’s what I did with the Veils and it worked brilliantly.

Hirst plans to create 90 paintings, including diptychs and triptychs

© Prudence Cummings

I’d like to know more about your subject—blossom—and where that comes from; it obviously has a long art-historical background.

Well, I did the Veil paintings, and then I thought they were more abstract, really, like trying to look through them to something beyond that, maybe looking out of a dirty window. They were obscuring but revealing at the same time, and they looked like flowers but they were very abstract.

Then, I just thought: “Oh my God, I wonder if I could just do cherry blossoms.” It seemed really tacky, like a massive celebration, and also the negative, the death side of things. Then I thought: “But what if I actually paint branches and I try and make them look like that?” I was a bit worried about it because it was representational. When you paint the branches first of all, they look like bad versions of Hockneys. So, I was thinking: “Shit, maybe this is a disaster.” But then, as I kept working on them and getting rid of the branches here and there and adding branches here and there, they started to have that feel. They seemed between something representational and something abstract, which I really like. It took quite a while to get to that.

I remember my mum painting cherry blossoms in the garden, when I was five or six. She had an oil painting of a cherry blossom and I remember I tried to paint it; I think I ate some paint.

Your mum was an artist?

I think she wanted to be an artist, but she didn’t like her art teacher at school, so she left school early. But she loved art. She painted—she used to do life drawings and stuff—but she was always ashamed of them and said: “Don’t look at that.” But, yeah, she’s really creative.

Are there any artists that are a particular inspiration? After I saw your Instagram post about your new paintings, I happened to go to the Courtauld Gallery and saw the Monet trees…

Definitely; Van Gogh as well.

And Pierre Bonnard?

Yeah, totally. Bonnard was absolutely an inspiration for the Veils. I went to see a show when I was really young. I used to go inter-railing when I was a student; we were looking at art, going everywhere. There was a brilliant show on at the Pompidou, which was decoding Bonnard.

I was studying art history, but not really having any money to go anywhere so, it was all from books. I remember that New York School Thames and Hudson book. As you’re looking at the dimensions and you’re imagining De Kooning, you’re looking at a really small image and thinking they’re big, and then I was doing big paintings in my garden and trying to create that, but without actually having seen any.

I’d seen a John Hoyland in the Leeds City Gallery. That was the first artist that blew my mind. So, I was looking at Hoyland, trying to imagine De Kooning and Barnett Newman and all that kind of stuff, and then when inter-railing came about, we went all over Europe, I think that’s a lot of what these paintings are about. They’re almost like De Kooning-scale Bonnards.

Splodges of blossom and leaf stamps—with blue background overpainting

© Prudence Cummings

Have you seen the Bonnard show at the Tate?

Yeah, amazing.

That Almond Tree in Blossom…

Yeah, exactly. I mean he’s brilliant: the colour on the inside, it’s just genius colour. The way everything moves is a physical thing; you’ve got to feel it. I always think, with sunlight on flowers, what else is there? They’re fluorescent; it’s beyond floral, it’s stupid, really.

Bonnard painted The Almond Tree just a week before he died, so there is an added poignancy.

It’s always a complicated thing, that, isn’t it? I remember John Berger’s book, Ways of Seeing, where he talks about Van Gogh’s painting the crows over the wheat field. He says it’s his last painting and then says: “Look how the painting’s changed now you know that.” Information changes things.

But there is something about when an artist gets to a certain age, and when they are painting things like this—blossom is so short-lived, and it can take on a potency.

There’s life and death in everything, isn’t there? I like the fact that Max Beckmann said that when he painted, he always primed his canvases black. He said that he sees the black as the void and then everything he paints is something he’s putting between himself and the void. So it’s a figurative painting with a conceptual background. I like that kind of conceptual thing.

And I suppose with the Veils, I was doing something like that—where you put something between you and something else. And then with the Cherry Blossoms, it’s even more so. I hope you can see the irony as well, because they feel like they’re celebrations of avoiding something.

Avoiding what?

I don’t know. Maybe it’s the darkness when I was in the shed in the garden painting. Colour is a good way to avoid darkness. But the celebration goes crazy, and you haven’t got time for the darkness. The colours remind me of all the diamonds on the diamond skull: thousands of shining diamonds.

Art’s always a celebration isn’t it? That’s the other thing people say: “Your art’s about death.” You just go: “It’s not; it’s about life.” Even though that’s semantics, it’s like not making art is death. You can’t really make art that’s negative because the process is so positive.

Hirst says that his decision to go back to the studio without having a final exhibition venue in mind—or a deadline—has benefited his work

© Prudence Cummings

You must be aware that at the same time you’re painting cherry blossom David Hockney is painting blossoms—apple, hawthorn—in Normandy.

I didn’t know about that, but I’m not surprised. We’ve got the same initials.

You have. Also, I find it interesting that the two iconic artists, in terms of the British public, David Hockney and Damien Hirst…

Now Tony Hart is gone…

Yes. You’re both doing this, while all this awful stuff—Brexit and the rise of the far right—is going on.

What the fuck can you do about all that stuff? It’s fucked, isn’t it? Brexit’s a joke, everything’s a joke, people in power are a joke. I’ve never really felt political in terms of my art. There’s a great political piece that Sylvia Plath wrote called Context and she said that the issues of our time influence her but only in a “sidelong” fashion: “My poems do not turn out to be about Hiroshima, but about a child forming itself finger by finger in the dark… Not about the testaments of tortured Algerians, but about the night thoughts of a tired surgeon.” And I always thought that’s a great way of looking at it.

But I suppose Picasso did Guernica, didn’t he? So there’s a time where you do want to come in. But when we’ve got muppets in the government falling over each other, there’s no logic whatsoever.

It’s so depressing, isn’t it?

Yeah, I think it’s time to paint cherry blossoms. That’s what they’re doing, so why can’t we?

Do you think they are painting cherry blossoms?

I don’t think they’re doing anything, actually. I think they’re just hanging on to power. I’ve never thought the people in power are idiots to the level they are now.

How formative was your experience of studying art at school and at art college?

I did a foundation course, which was the greatest thing. I think everybody should do one, whether you become an artist or not. I remember there was someone who was 60 on the course; I went straight from school, almost. It was only a year but it just blows your mind. There’s older people, younger people—a big mix—and people who were doing everything: graphic designers, fashion designers, textiles. It was just really brilliant. If you ended up being a bank manager, I think it would be great to have done a foundation course.

I’m just incredibly lucky to be healthy, to have an arena where whether people like it or don’t like it, it’s considered. Leeds University has a library which is just art; I remember being in there looking at all the books thinking that I had to read everything before I can begin. And then I thought I’d never ever get a book with my name on it. But I should try anyway; it would be amazing to have a book with your name on it on the shelves.

When I was around 15 I saw David Hockney. I’d gone to see a show of his in Bradford with a friend of mine when I was thinking I’ve got to be cultural in some way. And Hockney was actually there. I was, like: “Fuck, that’s David Hockney.” I remember thinking maybe I should get him to do me a drawing and I could sell it. I thought he’d do me one worth millions and millions; I just didn’t know.

Maybe he showed you the way.

Yeah, well he was Bradford, and I grew up in Leeds. I suppose there’s something about fame and celebrity which is important—knowing he was part of what I was into. But I got more from the Beatles.

Do you have any relationship with him now?

I’ve met him a few times; he did my portrait once. He had a studio in London at the time. I think it was in the 1990s.

You said that you didn’t want your cherry blossom paintings to look like “bad versions of Hockneys”.

Well no. I kind of do. I mean, they are over the top so I don’t want them to be tasteful. I want them to get hold of you. And it’s like you can get away with anything if they get hold of you. You know, blossoms are ridiculous; I want them to feel ridiculous. I want you to fall into them and be overwhelmed by them. And I think that scale’s important.

Remember when in the 1990s I was doing those Visual Candy paintings? This is what I was probably trying to do then. But it’s funny, I looked at those recently and I realised that at the same time I was doing giant spot paintings, all of those Visual Candies were quite small. I didn’t have the courage of painting them in that way but I came from that background, I wanted to be an abstract painter and I wanted to be big and gestural, but I was doing minimal spot paintings and then I thought: “Fuck it, I’m just going to do this because this is what I wanna do.” And then I reduced the size to chocolate-box-sized things. But they don’t really work at that size. You’ve got to really go for it. I suppose, over the years, I’ve realised that.

I’ve thought of a couple of things that Hockney said to me as well that were really funny. He’s got a brilliant sense of humour. He said to me: “Do people ever say to you how long will your work last?” I said: “Yeah, I get it all the time.” He said: “And what do you say to them?” I said: “Oh, you know, I say this and that.” And then he said: “You know what you should say?” And I said: “What?” He says: “Longer than you!”

Hockney calls the week in May that all the blossoms come out “action week”.

Yeah. I did that show of cherry blossoms called Two Weeks, One Summer in 2012. That’s how I ended the dark paintings. Because it is just two weeks in the summer, when they come out. And again I had the same thing where I had to rush like mad and paint all the paintings. But they’re really dark paintings with dead babies in jars with birds. It’s called Two Weeks, One Summer because the blossom just linked everything.

With this cherry blossom series, you said you are aiming at 90 works.

Yeah, 90 including multi-panels. I’ve got diptychs and triptychs.

Why 90?

I did a plan of all the multi-panel works; I just drew it out of what would be good to do if you imagine a show. I thought, I just want to make enough, really, so you get it out of your system. And then I just drew lots of sizes, lots of things I wanted to make, and realised with some I’m repeating myself and others I’m not.

I started off doing endless series, and then it becomes a bit complicated, so I think keeping it under 100 feels nice. They work differently; there’s lots of different colours, lots of different blossoms, lots of different shapes and sizes. You think you can just go into it, create it, get out the other end of it. Because the main thing is, what’s new for me is not making any more after this. It’s a massive amount of activity.

Do you have any idea of where you want to show them?

No. We have been talking to museums in Paris and Rome; they might do something in there with their collections. That’s the joy, really, of finishing them before you do anything, because you can look at different places. Or not show them; you can just wait. There’s a big switch that can happen if you’re not careful because you start saying: “Right, well, I’m going to complete the series.” And then somebody comes along and says: “I want to do a show.” And you’re halfway through the series and then suddenly you’re rushing for a show instead of finishing the series and working out what you want to do.

There was a time when I didn’t have a studio and I used to love the pressure. It worked for a while and then I started making mistakes and I had to get a studio. It’s a great place where you can try things out. With a lot of these, I’m going in and painting the background again because I’ve overdone it. I wouldn’t have had time for that if I’d have agreed to a show.

You need time to make things, and also time to consider them. I think that’s really important. You don’t want to show things before you believe in them.

So it’s like a limited edition…

I think you can make as many as you want as long as you’re clear and I think what’s happening in my market is that I wasn’t clear. The galleries were not clear, either. You give the galleries one and the collector says: “How many are there?” And they say: “Not many; you better buy it quick.” And then they find out there’s another one and they feel cheated. You can say there’s a thousand, as long as you say it at the point when they’re buying them and as long as you’re clear.

Is it difficult for you to separate what you’re doing and how buyers will approach it?

No. If you make good art people will want it; you just have to believe that. And even if they don’t, you can’t really think too much about buyers because you’re making art for people who haven’t been born yet, in a way. You’ve got to just go with what you believe in because that’s going to be the best chance of making things that are going to work. Usually, if I think about people buying things, it goes wrong.

I would never have made the shark if I was thinking about people buying things. Or spot paintings on the wall. I mean, even the size of these would have to have been a lot smaller; with the Veils, people have not got walls that size. Once you’re thinking like that, that’s about life, not money.

I hope so.

Yeah, well I think it is. I mean, I’ve doubted it at times in the past, especially coming from no money in the beginning. I remember with the Saatchi Gallery, when Saatchi was first buying all that art and stuff, there were people at my art school saying it was affecting art values with buying power. And everyone was up in arms about it. But I think at the end of the day if you make art that you believe in and it’s robust enough, it can withstand that. You have to believe that. And you have to believe that the currency is art and not money. That is why people pay a lot of money for it.

But now it’s all got a bit ridiculous, hasn’t it?

I don’t know. I suppose if someone wanted to pay the same for a single painting of mine as they would for a Picasso I’d be worried.

And a Leonardo for $450m?

It’s an odd one, isn’t it? I think I sort of stop at 150 for a great Picasso; there are enough people in the world to make that make some sort of financial sense. But anything above that I get a bit spooked.

Yes, it’s a spooky painting, too, I think.

I don’t know. I prefer a Richard Dadd.

Which are your favourite Old Masters?

I like the messier painters: Rembrandt, Goya, Titian, Soutine.

And what about sculptors?

Bernini. Michelangelo. I mean, they stand above everyone else, really.

So, in a way, having your cherry blossoms in Rome would be a match made in heaven.

Yeah, I thought maybe some of the Treasures corals might be good to exhibit with them as well: link the blossom tree paintings to sculpture and the way that the coral grows and hang them over the corals.

[ad_2]

Source link