ART WORLD NEWS

Harvard’s sublime show makes you see Bauhaus everywhere

[ad_1]

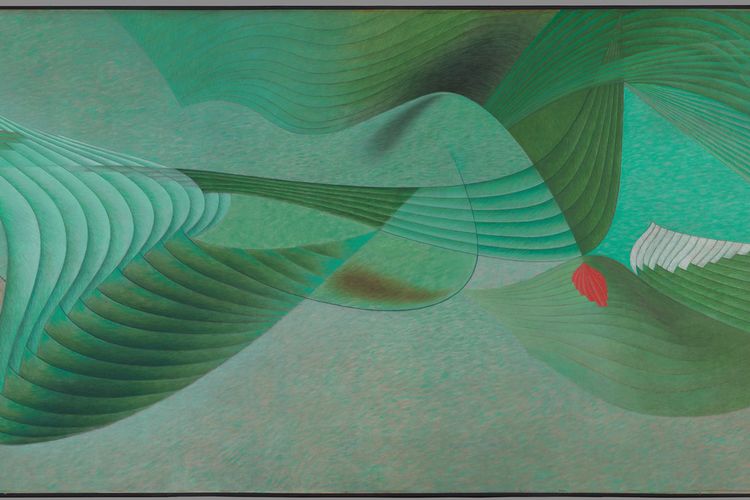

Herbert Bayer, Verdure (1950), commissioned for the Harvard Graduate Center’s study hall

Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum,

Harvard University has a long history with the Bauhaus artists, many of whom fled Germany when the Nazis took power and landed, one way or another, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. But it has not done a show from its 32,000-object Busch-Reisinger Museum archive since 1971—until now. For the movement’s 100th anniversary, the Harvard Art Museums have organised a sublime, important exhibition to honour it, The Bauhaus and Harvard (until 28 June 2019).

So what is Bauhaus? The term literally means “building house” but the movement started as a school, so it is best to think of it as the “building school”. The first critical ingredient in Bauhaus is that it demolished boundaries. Everything, in one way or another, from houses to pottery to carpeting, is built. The best of the Bauhaus artists, therefore, worked across categories: Anni and Josef Albers, Herbert Bayer, Marcel Breuer, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and, of course, Walter Gropius, who led the way when he came to Harvard to teach architecture in 1937.

Bauhaus, we learn, is richly various. It is also never frilly, sentimental, or fake.

The show is perfect for a teaching museum. Bauhaus was originally a school in Weimar, then Dessau, and most of the artists in the show either taught or studied there. The theme of mentors and protégés is just below the surface, that give and take between talented teachers and smart students that make both better. We see the senior masters like Gropius and Klee mold their students, like Anni Albers, and then give them the freedom and confidence to find their own vision. Albers did plenty of fabulous work, but among her achievements was adapting Bauhaus philosophy to 1950s and 1960s mass production.

Adèle Jackson Kaars-Sypesteyn, Untitled student exercise from Newcomb College (1942-49)

Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Gift of Professor R.D. Feild

The show starts in 1919 Germany, where Weimar’s municipal art schools, which historically separated fine arts like painting and sculpture from applied arts like design, merged. This radical idea demolished hierarchies that once elevated, for instance, painters and sculptors above architects, weavers or furniture designers. Courses were based on materials—wood, metal, wool, paper, pottery—and what I call “properties”, like texture, pattern, and colour.

The Bauhaus style probably evokes to most people Minimalist, linear, cerebral design, sleek and taut, eminently practical and, at its purest, ascetic and dry. The show at Harvard swiftly suggests we put this image aside. A selection of colour offset lithograph postcards from 1923 does the job, each designed by one of 20 students and teachers who had their own spin on the Bauhaus look. Some, like Dorte Helm, produced a trademark product: spare and geometric. Lyonel Feininger’s, however, is a dense maze of blocks and looks like a medieval cityscape, Paul Klee gives us a rich palette, and Georg Teltscher a dynamic, kicking and twisting figure. Bauhaus, we learn, is richly various. It is also never frilly, sentimental, or fake.

The curator, Laura Muir, has conceived an intelligent, attractive display. Big things like Bayer’s 20ft-wide mural Verdure, commissioned by the university in 1950, provides a compelling anchor. It is in the first gallery, which concerns Bauhaus teaching methods from the 1910s and 20s, but is placed on the back wall so that viewers see it at the end of a long vista. Bayer painted it for a new Harvard Graduate Center study hall, so it acts as a denouement of the Bauhaus learning experience. I has also just been cleaned so its dozens of lusciously abstract greens look fresh, shattering all preconceptions of Bauhaus art as arid.

Anni Albers, Design for a Rug (1927)

Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Gift of Anni Albers

The textile artist Anni Albers has been given a well-deserved place of pride in the exhibition, and while most visitors may know her husband Joseph better, she is the golden thread running through the show. Anni Albers studied with Klee in the 1920s. The show displays her evolution from that point, such as her powerful Design for a Rug from 1927, through to 1949. (The Bauhaus’s weaving work was almost entirely done by women, a gendering-by-medium that was unusual since the movement was more open to women than most artist groups.) Albers, who went to Yale with Joseph in 1957, had an unerringly subtle command of colour, texture, and rhythmic pattern. She was among the key designers involved in the new Harvard Graduate Center constructed in 1949-50, the university’s first Modernist building. By creating textile room dividers, she found a perfect balance among sound-proofing, ease of opening and closing, neutrality, and handsomeness.

Surprises? I love them. What is the point of seeing a show that merely confirms what you already know? I knew, for instance, next-to-nothing about Bauhaus photography. Werner Feist’s Kurt Stolp with Pipe (1929) is just about the most striking portrait I have seen in a long time, a tight close-up, starting with Stolp’s stubbly chin—a whisker jungle—and climbing up his face as if it is a mountain. Marianne Brandt’s collage, Untitled with Anna Mae Wong (1929) is so wild and unexpected that the image is barely contained by her disciplined Bauhaus structure. It is a study in exoticism, that embraces not only the movie star Wong, who later was in King Kong, but a zebra, metal rivets, and glass.

Werner David Feist, Kurt Stolp with Pipe (1929)

Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Gift of Josef Albers

I once thought Joseph Albers was cold and bloodless but over the past few years, I have seen too many of his works that challenged me, and I have warmed to him. His small, Overlapping (1927), a stained glass panel with opaque black on milky glass, is gorgeous and strangely intimate.

Harvard was not the only place steeped in Bauhaus, though, and the fascinating H. Sophie Newcomb College in New Orleans figures in this show too. A pigment tone collage used in classes there in the 1940s is a whimsical though effective teaching tool.

And here is another measure of the overall Bauhaus effect and the show’s strength: I went to the Bauhaus exhibition first, walked through the museum’s splendid permanent collection galleries, had lunch, went back to Bauhaus, and then hit the antiquities and contemporary galleries. Bauhaus design was impressed in my head as I looked at every object from every era. Though I have seen many of these things a hundred times over the years, The Bauhaus and Harvard prodded me to see them differently, with refreshed eyes. That alone tells me it is a great show.

[ad_2]

Source link