ART WORLD NEWS

Michelangelo for beginners, and a new view of the master’s bronzes

[ad_1]

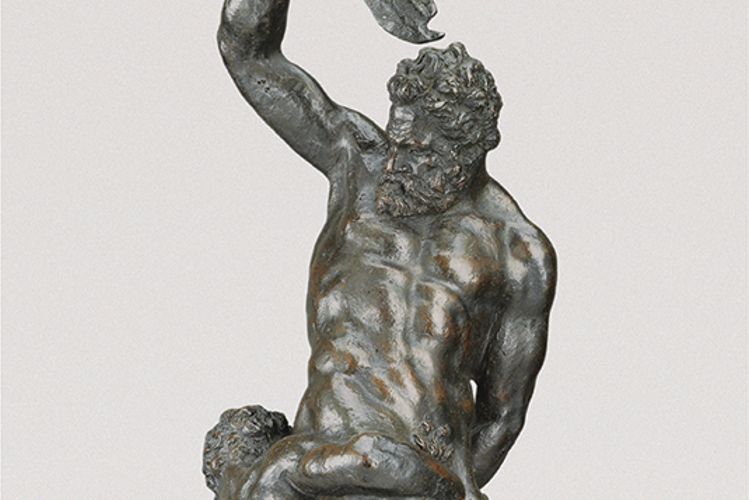

Bronze as a way of preserving original works: After Michelangelo, Samson and Two Philistines, a 16th-century cast from a lost model (around 1528-31) by Michelangelo

Courtesy of the Frick Collection, New York

Michelangelo’s fame is witnessed in such hallowed works as the Pietà (1498-99) and Moses (around 1506-13) executed in Rome, and the David (1501-04) in Florence, each hewn from an individual marble block. As Michelangelo himself wrote: “The greatest artist does not have any concept which a single piece of marble does not itself contain within its excess.” David excepted, carved from a block botched by an earlier sculptor, Michelangelo attended to the supply of marble for the majority of his sculptural and architectural projects, as demonstrated in his numerous surviving block drawings. William Wallace established his scholarly reputation by elucidating these practical sketches and reproduces two in a book otherwise aimed at a novice audience. The unquestionable profit from the author’s distilled erudition must be set against illustrations of uneven quality, often unkindly cropped.

Best known for The Sexuality of Christ (1984), Leo Steinberg was a maverick art historian with a taste for polemic whose Michelangelo’s Last Paintings (1975) on the Pauline chapel frescoes remains as unvisited as the frescoes themselves. Posthumously collected in Michelangelo’s Sculpture: Selected Essays are five previously published articles and two unpublished lectures, attentively edited and freshly illustrated. Steinberg repeatedly focuses on the three pietàs spanning the artist’s career—the Roman, the Florentine (around 1547-55) and Rondanini (1552-64)—as well as the Medici Madonna (1521-34), works offering the resonance of a divine mother-and-child relationship in life and death, as well as abundant visual precursors and sequels from antiquity to the 20th century. Compositional details such as Christ’s “slung leg”, seen in all four works, are what Steinberg calls “anatomy as theology”. For Steinberg the realisation of such meaning-laden motifs fulfils Michelangelo’s intention; the material contingencies of marble are largely ignored. Steinberg is worth reading, however, less for Michelangelo, more as idiosyncratic response.

In contrast, artistic process is to the fore in Victoria Avery’s ambitious publication on Michelangelo as a sculptor of bronze, an overlooked topic given that both the artist’s large-scale sculptures in this medium—a standing David (1504-08) and a seated Pope Julius II (1506-08)—perished. Avery presents a wealth of research on Michelangelo’s brazen achievements, including the information that Michelangelo cast Julius in two pours of metal molten from an astonishing 7,200kg of alloy—the cost of the material serving to augment the prestige of the pontifical personification. The valued integrity of the single block was mirrored in the way Michelangelo cast Julius whole, employing the lost wax process to make a hollow sculpture of great tensile strength whose surface detail the artist laboriously chased himself.

To this lost oeuvre Avery wishes to add two pendant bronzes, each depicting a male nude with arm raised astride a panther, the figures and animals separately cast in apparent contradiction to Michelangelo’s sculptural credo (and raising the question as to whether the beasts were conceived with riders). Destined for an unknown wealthy patron, the bronzes are named after Adolphe and Julie de Rothschild, who acquired the previously undocumented works in 1878 at a sum reflecting a traditional attribution to Michelangelo. They then receded from view to reappear at auction in 2002 and impress Paul Joannides with their Michelangelesque musculature. Joannides subsequently linked the bronzes to an outline sketch of a twisting naked youth riding a leonine cat, a copy of a lost drawing by the master of speculatively sculptural scope. This persuaded Joannides to attribute the bronzes to Michelangelo, echoes of the early Sistine sibyls in the nudes’ mirrored poses and powerful torsos suggesting a date of around 1506-08. An otherwise distracting commission becomes an opportunity for Michelangelo to acquaint himself with the complexities of bronze work on a manageable scale.

Michelangelo mostly never intended his bronzes to be bronzes. His surviving works in this medium derive from now lost preparatory models in wax or clay cast subsequently, such as the fragmentary Bargello River God or the finished Frick Samson and Two Philistines. Michelangelo must have also modelled statuettes with the purpose of casting them, but examples such as the Victoria and Albert Hercules Pomarius are putative. The Rothschild bronzes would be a hitherto unexampled category of privately commissioned bronzes. Avery employs the insights gained in the making of a replica of the elder nude to argue that Michelangelo was responsible not solely for the completed models but every stage of the subsequent production (similarly to Julius): this includes the cold work and distinctive hammering of the riders’ brassy surface, although the modelling of the younger nude is noticeably inferior, the result of imperfect casting. Detailed comparison of the elder nude’s anatomy with a flayed cadaver reveals not just the remarkable anatomical accuracy of the body in bronze, but also the matched concerns in Michelangelo’s autograph drawings, the circles on the thigh of the British Museum’s Haman (1512) coinciding with the longitudinal sartorius muscle also seen in the bronze. Innovative neutron imaging of the thick-walled but hollow bronze casts suggests the employment of a bell founder rather than a specialist as developed later in the 16th century.

Dissenters to Avery’s thesis attribute the bronzes to a mid 16th-century imitator—part of the bronzes’ enigmatic function would thus lie in their very similitude to Michelangelo. Whether the attribution solidifies or liquefies, this significant publication makes clear that sculpting in bronze was a thoroughly mediated process, the alchemical fusing and casting of alloy being of complex command. It is this, surely, rather than the theoretically additive nature of the technique, which caused Michelangelo in 1523 to observe that bronze sculpture “was not my art”.

Daniel Godfrey is a curator of prints and drawings, now working on Charles Booth-Clibborn’s collection of German Romantic graphic art. He co-edited the catalogue for the exhibition of the collection at the Klassik Stiftung, Weimar (2013), and has worked on exhibitions at the British Museum

- William Wallace, Michelangelo: a Portrait of the Greatest Artist of the Italian Renaissance, André Deutsch/Carlton Publishing Group, 160pp, £25 (hb)

- Leo Steinberg, edited by Sheila Schwartz, Michelangelo’s Sculpture: Selected Essays, University of Chicago Press, 320pp, £49, $65 (hb)

- Victoria Avery, ed , Michelangelo: Sculptor in Bronze, Philip Wilson Publishers, 320pp, £75, $95 (hb)

[ad_2]

Source link