ART WORLD NEWS

Part-exchange Picasso and a cut price Van Gogh: antics of an art dealer

[ad_1]

It was R.B. Kitaj who, witnessing my efforts on the easel next to his at the Ruskin Art School in Oxford, first suggested that I should become an art dealer not a painter. He told me to get tickets for the sale of the Goldschmidt Collection at Sotheby’s in October 1958, an auction of just seven paintings that was to change the course of the art market.

That was Peter Wilson’s first sale as Sotheby’s chairman and all the paintings made records, although just before he knocked down Cezanne’s Le Garçon au Gilet Rouge for £276,000 (the equivalent of around £6.3m today), Wilson languidly asked: “Will no one bid me anymore?”. The very first painting, an Edouard Manet self-portrait, was knocked down to a “Mr Summers”—luckily not me, but the nom de plume of John Loeb.

Aged 21, I plucked up courage and walked up the stairs to Tooth’s Gallery on Bruton Street. Unusually, Dudley Tooth was alone in the gallery and we got into a long conversation. He took down my address and two months later I got a letter offering me a job, as a trainee salesman at £550 per year. Hardly a fortune, but what an opportunity.

Those were different times—Dudley would take me to Paris for a week, twice a year, to buy “stock”, returning with maybe a dozen paintings by Pissarro, Sisley, Corot, or Boudin, sometimes a Degas bronze or two. Imagine doing that now.

Certain clients stick in the mind. In 1964 I sold a Fauve painting by André Derain to the Houston collectors John and Audrey Beck, but then the French government decided to rescind the export licence—something the vendor said was our problem not hers, as we had “shaken hands”. John and Audrey decided simply to buy a house in France, keep the painting there and let the dust settle. Years later they got the export licence and the painting now hangs in the Beck wing of the Houston Museum. Are there many clients like that today?

Still in 1964, Christie’s asked me to go and set up a New York office; the salary was generous, but my new wife was not keen on the seven-year contract. However, three years later, Gerald and Desmond Corcoran offered me a partnership at the Lefevre Gallery next door to Tooth’s—an offer I could not refuse.

The Lefevre Gallery, or Alex Reid and Lefevre, had existed since the two great rivals agreed to amalgamate in 1926. At the end of the 19th century, Alex Reid worked in a Parisian gallery alongside Theo Van Gogh who introduced him to his brother, Vincent. Reid and Vincent ended up sharing a flat for six months where Van Gogh painted three portraits of him, one of which he sent back to his father who reputedly disliked it so much he threw it away. Another we later sold to the Glasgow Art Gallery. In his depression Vincent suggested a joint suicide pact, but Alex was not ready, so Vincent went South to Arles while Reid stayed on in Paris.

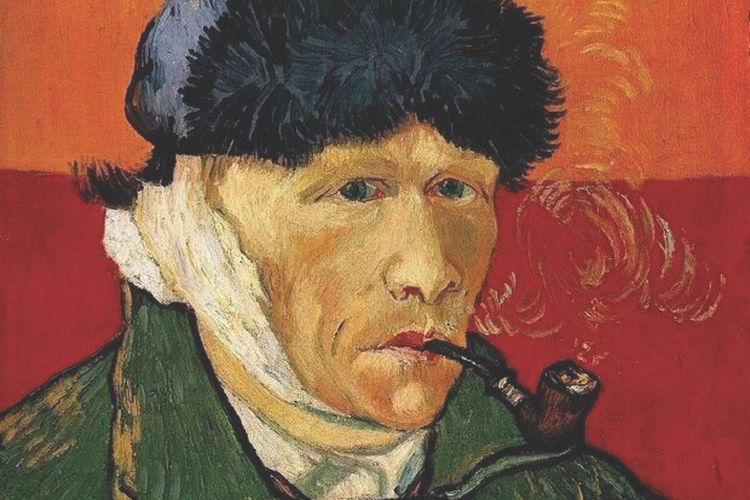

Vincent van Gogh’s Self-portrait with bandaged ear and pipe (1889)

Courtesy of Niarchos Collection

Yet Van Gogh’s association with Lefevre endured. In 1971, with some other dealers we managed to buy Van Gogh’s Portrait of a Peasant (Patience Escalier) before it came up for sale at Christie’s. We put a big price on it and everyone thought it too expensive. The shipping magnate and collector Stavros Niarchos had his curator, Mark Zervudachi, look at it every few months and, over a year later, he made us an offer that we had to take.

Shortly after, with the same team, we were able to buy Van Gogh’s Self Portrait with Bandaged Ear and Pipe (1889). We invited Stavros to lunch and showed him the painting, quoting what we thought was a stiff price—between $2m and $3m. He never discussed the painting at lunch, but on leaving casually said: “I’ll take it”. No bargaining—we could have named any figure.

We never would have guessed then at the astronomic prices of today—and few, if any, dealers can afford to handle such works now.

Back then, it was still a time of discoveries. Around 1973, Mme. Hebrard, the widow of A.A. Hebrard, who had cast all the bronzes of Degas between 1919 and 1922, died in Paris. In her basement were found a near complete set of Degas bronzes (71 of 74) with the founder’s mark “Modele”, including Petite Danseuse de Quatorze Ans (Little Dancer Aged 14). Realising that the plasters and waxes would suffer during the casting process, Hebrard had used the “Modele” set as the matrix for the full casting and never told anybody.

We got wind of this unknown set and asked John Rewald to come and see them. He authenticated them as being Hebrard’s test casting so we bought them and I offered them to Norton Simon. He rang back immediately and told me to catch a plane to Los Angeles leaving in four hours, and bring bronze No. 32, Girl examining her right foot, with me. I just made the plane and met Norton with Daryll Isley, his curator, in a booth at the Polo Lounge of the Beverley Hills Hotel. He handed me his bronze No. 32 and took mine. “Yours is a fake,” he said. “No, it’s not,” I replied, “but yours is”. And so it was. The whole collection of Hebrard bronzes is now in the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena.

Slipping up

Sometimes even the most experienced dealers can make an error of judgement. In the mid-1970s, the German art dealer and collector Heinz Berggruen fell in love with a Cezanne still-life that we had, priced at $2m. Having a rare moment of illiquidity, he asked if we would take a substantial amount of cash, plus a Picasso. That Picasso turned out to be the Harlequin with a Mirror (1923). We agreed and shortly afterwards, offered the Picasso to Hans Henrik ‘Heini’ Thyssen for $2.5m. And, without hesitation or bargaining, Heini said: “Ja, I will take it.”

Picasso’s Harlequin with a Mirror (1923): “We sold the painting too quickly,” says Summers

Courtesy of Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza

Heinz gave up a true masterpiece, we sold the painting too quickly and Heini came out best—I cannot begin to imagine what it is worth today.

Some of my fondest memories involve impromptu moments with the artists themselves. In 1989, following the death of his long-time dealer Pierre Matisse, we were asked to become Balthus’s agents. Balthus had befriended Lucian Freud in Paris in the late 1940s and when, in 1989, Lefevre Gallery held an exhibition of paintings by his wife, Setsuko Klossowska de Rola, I invited them all for an evening cruise on my boat, Bluebird of Chelsea. However, it rained so hard that we had to sit below. I gave them each a sheet of paper and a pencil and they started sketching each other. Unfortunately, the motion of the boat didn’t help their draughtsmanship. We all laughed and Balthus agreed to destroy his drawing. But some years later I was a little surprised to see Lucian’s drawing of Balthus on Bluebird exhibited in a New York gallery.

Now, at 80, I have become a compulsive painter myself. My first exhibition, opening this month at Sladmore Contemporary on Bruton Place (15-24 May), is coincidentally a stone’s throw from Bruton Street, where I spent over 40 years as a dealer. Poacher turned gamekeeper, you might say.

[ad_2]

Source link